Written By: Sheeraz Zaman Lone

The suicide bombing at the Khadijatul Kubra Shia Mosque on the

outskirts of Islamabad in February 2026 represents a critical inflection

point in Pakistan’s long and troubled encounter with terrorist violence,

sectarian exclusion, and the blowback from decades of instrumentalising

non state armed actors in regional politics. It encapsulates at once the

acute human tragedy of mass casualty terrorism, the strategic volatility

of cross border terror, and the structural vulnerabilities of a state that has

yet to fully reconcile its constitutional promises of equal citizenship with

deeply embedded sectarian hierarchies and competing security

imperatives.

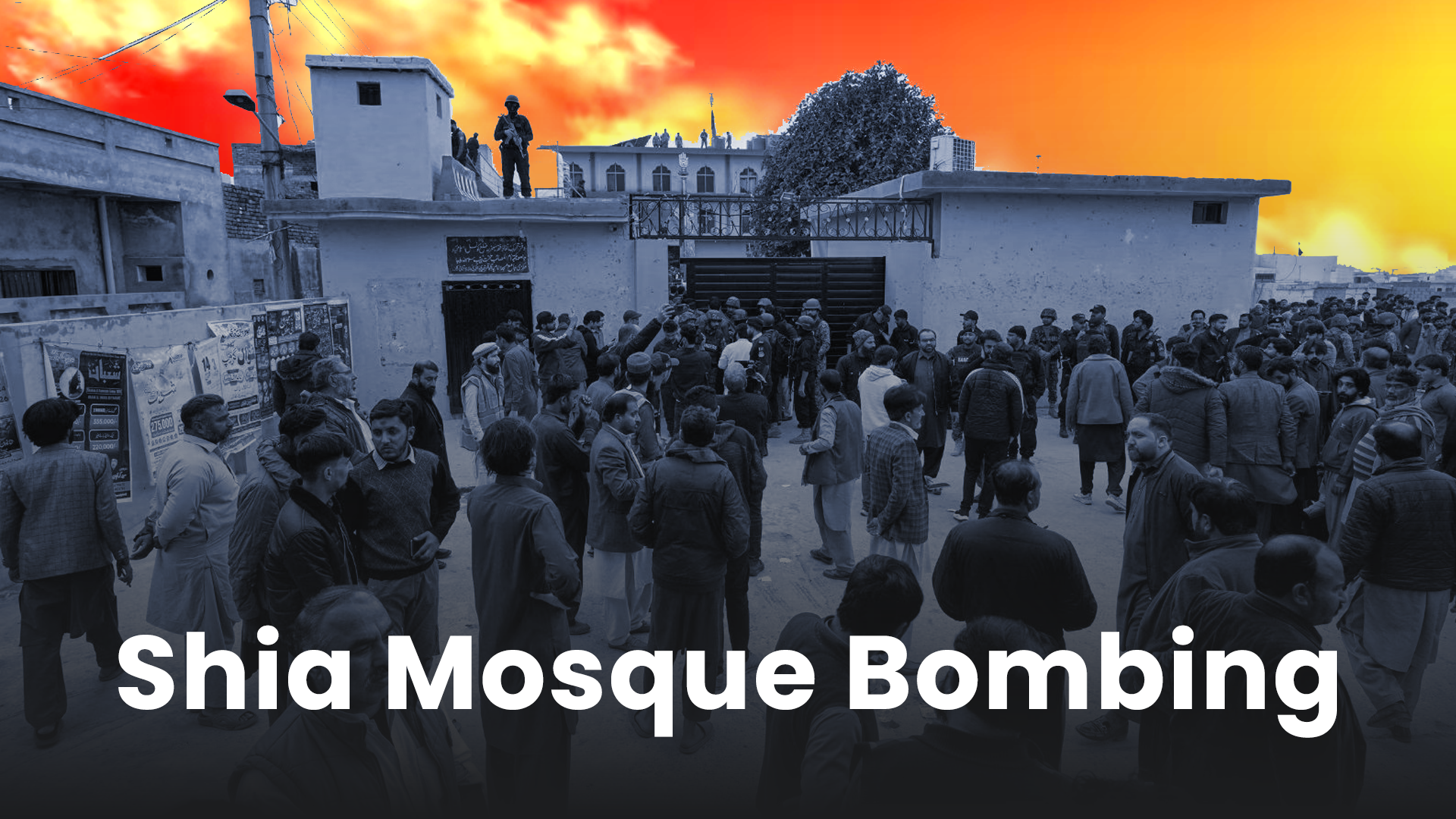

The attack itself, by most accounts, is now relatively well established in

its basic factual outline, even as important investigative details remain

under active scrutiny. On Friday 6 February 2026, during congregational

prayers at the Khadijatul Kubra Mosque (also referred to as an

Imambargah) in the Tarlai Kalan area in southeastern Islamabad, a

suicide bomber attempted to enter the compound but was reportedly

confronted at the gate by mosque security personnel. Witnesses and

official statements converge on a sequence in which the assailant

opened fire on the guards and then detonated an explosive vest either at

the inner gate or within the mosque precincts, producing a devastating

blast that collapsed parts of the structure, shattered windows, and left

bodies and wounded worshippers scattered across the prayer hall and

courtyard. Initial casualty figures varied in the chaotic aftermath, but

Pakistani officials subsequently reported between 31 and 32

worshippers killed and around 169–170 injured, with a significant

number in critical condition; some later reports and political statements

have used slightly higher figures, underlining how casualty counts in

mass attacks can evolve as victims succumb to injuries and as

institutions consolidate data. Hospitals across Islamabad were placed on

high alert, emergency services appealed for blood donations, and

televised images showed residents and police jointly transporting the

wounded to nearby medical facilities in a desperate effort to prevent the

death toll from rising further.

The attack rapidly drew a claim of responsibility from a local affiliate of

the so called Islamic State, identified in various reports as Islamic State

Khorasan (ISIS K) or the Islamic State in Pakistan Province (ISPP),

illustrating the fluid branding and organisational overlap within Islamic

State’s regional project. Through its Amaq news agency, the group

disseminated a statement and an image of a gun wielding attacker with

his face covered and eyes blurred, celebrating the operation and

describing it as a “fidayeen” suicide mission against what it casts as

heretical Shia targets. Pakistani and international monitoring

organisations tracking jihadist messaging noted that the claim was

consistent with prior ISIS K operations in Pakistan and Afghanistan that

similarly framed Shia communities as legitimate targets of mass violence

in a transnational sectarian campaign. Subsequent reports cited

Pakistani officials as identifying the bomber as a Pakistani national who

had reportedly travelled repeatedly to Afghanistan, an observation that

fed directly into a broader debate about the cross border dimensions of

terror networks and the degree to which Afghanistan based sanctuaries,

funders, or facilitators are involved in attacks on Pakistani soil.

In the hours and days following the bombing, the Pakistani state

mobilised security and symbolic responses that reflected both the gravity

of the incident and its political sensitivity. Islamabad authorities imposed

heightened security measures, increased checkpoints, and placed key

installations on alert, while political and religious leaders issued

condemnations and calls for unity against terrorism. Prime Minister

Shehbaz Sharif and President Asif Ali Zardari both framed the attack as

an assault not only on a vulnerable religious minority but also on

Pakistan’s national cohesion, pledging that those responsible would be

pursued and insisting that terrorism would not be allowed to derail the

country’s trajectory. Thousands of mourners gathered for funerals and

prayer ceremonies for the victims, with media reports of “mourning in

every street” underscoring the depth of communal grief and the sense

that an especially egregious threshold had been crossed in the capital,

which has historically suffered fewer large scale attacks than provinces

such as Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan. The bombing was widely

noted as the deadliest attack in Islamabad since the Marriott Hotel truck

bombing in 2008, and also as the second major attack in the federal

capital within a few months, following a suicide bombing near a district

court in late 2025 that killed at least a 12 people.

The investigative response developed rapidly, though inevitably amid

contested narratives. Pakistan’s interior minister Mohsin Naqvi

announced that security agencies had conducted coordinated raids and

apprehended four suspects in connection with the bombing, including an

individual presented as the alleged mastermind. According to this

account, the arrests occurred across multiple locations and targeted

what authorities described as a facilitation network supporting the

bomber, suggesting that the operation involved local logistical support

rather than a purely “external” attacker. Parallel reporting from Peshawar

indicated that police had raided what they termed the hideout of the

suspected bomber, detaining two brothers and a woman, and seizing

material believed to be linked to the planning and preparation of the

attack. While detailed forensic and judicial findings were still emerging,

the official narrative increasingly emphasised cross border linkages:

defence minister Khawaja Asif publicly stated that the bomber had

travelled between Afghanistan and Pakistan and that the incident should

be understood in the context of a wider pattern of attacks with origins, or

at least enabling environments, across the Afghan frontier.

It is within this context that Pakistani officials advanced the controversial

claim that “India backed proxies” were involved in enabling or

sponsoring the attack, with senior ministers alleging that Islamabad had

shared evidence of Indian support for terrorism with neighbouring

countries. These assertions provoked immediate and forceful rebuttals

from India, whose Ministry of External Affairs issued a statement

condemning the bombing, expressing condolences for the victims, and

dismissing Pakistan’s accusations as baseless attempts to externalise

responsibility for domestic security failures and “home grown ills.”

Afghan authorities and commentators likewise rejected implications that

Kabul was complicit in cross border militancy, even as international

analysts noted persistent concerns over the ability or willingness of the

de facto Afghan authorities to constrain ISIS K and other transnational

jihadist groups operating from Afghan territory. This triangular blame

game between Islamabad, New Delhi, and Kabul illustrates how

dramatic acts of terror are quickly subsumed into regional geopolitical

contests, often at the expense of a sober analysis of the local drivers of

violent extremism and the internal policy reforms required to address

them.

From an academic perspective, the February 2026 bombing must be

situated within at least three overlapping trajectories: Pakistan’s long

history of sectarian violence targeting Shia and other religious minorities;

the evolution of ISIS linked networks in South Asia; and the “blowback”

from Pakistan’s decades long reliance on militant groups as instruments

of foreign and domestic policy. Pakistan has witnessed recurrent mass

casualty attacks on Shia mosques, processions, and shrines, as well as

on Ahmadis, Christians, Hindus, and Sufis, particularly since the 1980s

when sectarian organisations such as Sipah e Sahaba Pakistan and

Lashkar e Jhangvi emerged within a regional environment influenced by

the Iranian revolution, Saudi Iranian rivalry, and the anti Soviet jihad in

Afghanistan. In more recent years, ISIS K and related entities have

sought to “outbid” older sectarian actors in brutality and international

notoriety, carrying out attacks such as the 2017 assault on the Lal

Shahbaz Qalandar shrine in Sehwan that killed more than 90 people,

and multiple bombings in Quetta and Peshawar directed at Hazara

Shias and other minorities. The Islamabad mosque bombing follows this

grim pattern of targeting Shia worshippers at sites of religious gathering,

but it is particularly significant in that it pierces the relative sense of

security that many Pakistanis associate with the capital and underscores

the diffusion of risk beyond historically “peripheral” conflict zones.

The logic of such attacks, in the strategic calculus of ISIS K and similar

groups, is at once sectarian, political, and performative.

Shia communities are framed as apostate and thus legitimate targets within

an exclusionary Salafi jihadist worldview, making Shia mosques and

religious rituals attractive sites for “spectacular” violence intended to

inflame intra Muslim tensions and undermine any prospect of pluralist

religious coexistence. At the same time, hitting the capital demonstrates

reach and embarrasses the state, signaling that, despite an extensive

security apparatus, Pakistan remains vulnerable at its political core and

cannot reliably shield its citizens from attacks even in highly policed

urban spaces. In the transnational market for jihadist prestige, such

operations help ISIS K project resilience and relevance after territorial

defeats in Iraq and Syria, offering a narrative of continued expansion into

new theatres and the ability to exploit cross border sanctuaries and

porous frontiers.

Yet an exclusive focus on the operational logic of ISIS linked actors risks

obscuring the deeper structural conditions that make such violence

possible and, in some respects, probable. Pakistan’s state narrative

frequently highlights the sacrifices of its security forces and citizens in

the “war on terror,” and it is true that Pakistan has suffered tens of

thousands of fatalities from terrorism over the past two decades.

Nevertheless, scholars and policy analysts have long argued that

successive Pakistani governments and segments of the security

establishment fostered and protected particular militant organisations as

strategic assets, especially in the context of Kashmir and Afghanistan,

while failing to dismantle sectarian infrastructure that served as a feeder

for more radical entities. This selective repression produced what might

be described as a “hierarchy of militancy,” in which groups considered

aligned with perceived national objectives enjoyed relative impunity,

while others were targeted more aggressively, creating complex

networks of overlap, splintering, and tactical alliances that are difficult to

control. Over time, the boundaries between “good” and “bad” militants

blurred, and younger fighters, socialised into a culture of militant

activism, sometimes defected to more radical outfits such as ISIS K that

explicitly reject the constraints of state patronage.

The Islamabad bombing therefore exemplifies how terror “plans” and

militant infrastructures cultivated or tolerated for strategic purposes can,

in the language of blowback, return to haunt the patron state itself. Even

if ISIS K is organisationally distinct from groups historically cultivated by

Pakistani actors, it operates within a milieu shaped by decades of

militarised Islamism, proliferation of armed jihadist networks, and the

normalisation of sectarian dehumanisation in parts of the public sphere.

Moreover, when officials respond to such attacks by deflecting attention

towards external conspirators, particularly by attributing responsibility to

India without making public detailed, independently verifiable evidence,

they risk reinforcing a political culture in which introspection about

domestic drivers of radicalisation is postponed or avoided.

The immediate political gains of such externalisation, rallying nationalist

sentiment or delegitimising adversaries, are offset by the long term cost

of under investing in deradicalisation, inclusive governance, and

institutional reform within Pakistan itself.

Religious exclusion functions in this context both as a discursive

resource for militants and as a structural vulnerability for the state.

Pakistan’s constitution formally guarantees equality of citizens and, in

principle, protects religious freedom, yet discriminatory laws and

practices, most notably the second amendment declaring Ahmadis non

Muslim, stringent blasphemy provisions, and pervasive social prejudice

against Shias and smaller minorities, have entrenched hierarchies of

belonging.

When segments of society internalise the idea that certain

communities are less authentically Pakistani or less fully Muslim, it

becomes easier for militant entrepreneurs to legitimise violence against

them as a form of purification or defence of the faith. At the same time,

victims of discrimination and targeted violence may lose faith in state

institutions that appear unwilling or unable to protect them, further

eroding social cohesion. The Islamabad Shia Mosque bombing thus

dramatizes how religious exclusion can be lethal not only for

marginalised communities but ultimately for the fabric of the nation state,

undermining trust, fueling cycles of retaliation, and providing adversaries

with exploitable fault lines.

International reactions to the bombing underline both the humanitarian

stakes and the geopolitical complexity of the incident. The United

Nations Secretary General and senior UN officials issued statements

condemning the attack, expressing solidarity with Pakistan, and

reiterating that places of worship must be protected as spaces of peace.

States including India and Afghanistan condemned the bombing and

expressed condolences, even as they repudiated Pakistani allegations

of external involvement and, in India’s case, explicitly framed those

allegations as an attempt to avoid confronting “home grown” extremism.

The Vatican and various Christian organisations also highlighted the

attack as part of a wider pattern of terrorism and religiously motivated

violence, calling for protections for all faith communities and for

international cooperation in countering violent extremism.

Analytical pieces from think tanks and security experts stressed that the bombing

should sharpen focus on the regional threat posed by ISIS K, whose

operations have increasingly crossed formal borders and challenged

both the Taliban government in Afghanistan and neighbouring states

such as Pakistan.

These international responses point to a broader question: what does

this attack mean for Pakistan in the present moment, and what are the

likely consequences if structural issues remain unaddressed? In the

short term, the bombing is likely to reinforce securitised approaches,

including intensified intelligence operations, extended use of special

powers by counterterrorism agencies, and potentially renewed kinetic

campaigns in border regions or perceived militant strongholds. While

such measures may be necessary to disrupt immediate threats, an over

reliance on coercion, absent parallel investments in inclusive politics and

social cohesion, risks reproducing the conditions under which groups

such as ISIS K recruit: communities feeling collectively punished or

discriminated against, lack of civilian oversight, and limited avenues for

peaceful political expression.

In the medium to long term, repeated high profile attacks on minorities

can deepen patterns of sectarian segregation, as vulnerable

communities retreat into defensive postures, reduce public religious

expression, or migrate internally or externally in search of safety. This

fragmentation undermines the idea of a shared civic space in which

Pakistanis of different sects and religions coexist as equal citizens, and it

can have economic and intellectual costs as professionals and

entrepreneurs from minority communities reduce their exposure or leave

the country. Simultaneously, persistent insecurity in the capital can deter

investment and tourism, strain public finances through increased

security spending, and exacerbate public dissatisfaction with

governance.

From a policy perspective, Pakistan has not been inactive. The state has

launched multiple counterterrorism campaigns, most notably operations

such as Zarb e Azb and Radd ul Fasaad, and has adopted national

action plans that formally commit to dismantling militant infrastructure,

regulating madrassas, and curbing hate speech. It has also banned

certain organisations and placed others on watchlists, made high profile

arrests, and cooperated with international partners on intelligence

sharing and border control. However, implementation has often been

uneven, with critics noting selective enforcement, a tendency to focus on

groups threatening the state directly while tolerating others seen as

tactically useful, and limited progress in reforming curricula or

addressing socio economic grievances that can feed radicalisation.

The Islamabad Mosque bombing, in this sense, should be treated as a

critical test of whether Pakistani authorities will move beyond episodic

crackdowns towards a more holistic, rights respecting, and inclusive

strategy. Comparative research on countering violent extremism

suggests several elements that would be particularly salient. First, a

consistent and unequivocal normative stance against sectarian hate,

including enforcement of laws against incitement irrespective of the

political connections of the perpetrators, is essential to delegitimise the

ideological ecosystem from which anti Shia and anti minority violence

emerge. Second, education reform that fosters critical thinking, pluralist

understandings of Islamic tradition, and appreciation of Pakistan’s multi

religious heritage can undercut the simplistic binaries exploited by

extremist propagandists. Third, community based approaches that

involve religious leaders, civil society organisations, and survivors of

terrorism in designing prevention and rehabilitation programmes can

enhance legitimacy and effectiveness.

Crucially, any sustainable strategy must also address the regional

dimension without reducing it to blame shifting. Pakistan is entitled, as

any state is, to raise legitimate concerns about cross border facilitation

of terrorism, whether emanating from Afghan territory or involving hostile

intelligence agencies. However, the credibility of such claims depends

on transparent presentation of evidence and willingness to subject them

to international scrutiny, rather than relying on rhetorical assertions that

are easily dismissed by neighbouring states.

At the same time, Pakistan’s own history of utilising non state actors must be openly

acknowledged and reckoned with, not only as a moral imperative but as

a practical necessity for rebuilding trust with neighbours and convincing

its own citizens that a genuine break with past practices has occurred.

Regional cooperation frameworks, whether bilateral mechanisms with

Afghanistan and India or multilateral platforms involving other South and

Central Asian states, should focus on intelligence sharing against ISIS K

and similar transnational threats, joint border management initiatives,

and measures to curb financial flows to extremist networks.

The Islamabad Shia Mosque bombing on 6 February 2026, then, is more

than a discrete tragedy; it is a stark indicator of the intertwined dangers

of militant blowback, sectarian exclusion, and geopolitical

instrumentalization of terror. The immediate facts of the attack, the

suicide bomber’s assault on worshippers, the scores of dead and

wounded, the claim of responsibility by an ISIS affiliate, the arrests of

suspected facilitators, are the visible tip of a much larger iceberg of

structural and historical dynamics that have long rendered Pakistan

vulnerable to violent extremism. Whether this moment becomes a

catalyst for a more self critical, inclusive, and regionally cooperative

approach, or simply another entry in a grim chronicle of recurring

violence, will depend on the choices made by Pakistan’s political

leadership, security institutions, religious authorities, and civil society in

the months and years ahead.